I Owe J.C.R. Licklider An Apology

Three years ago, I wrote a blog post that I was and remain pretty proud of. It was titled Networks, Information, Engagement & Truth and in it I described the influence that two great American thinkers have had on my own thinking of the power of computer networks to advance and improve our political process, and the threat of ‘bad information’ that could yet undermine it all.

One of the two mentioned thinkers was Thomas Jefferson. But I need to focus further on the other, J.C.R. Licklider. This is how I described my introduction to ‘Lick’ and his work in that blog post;

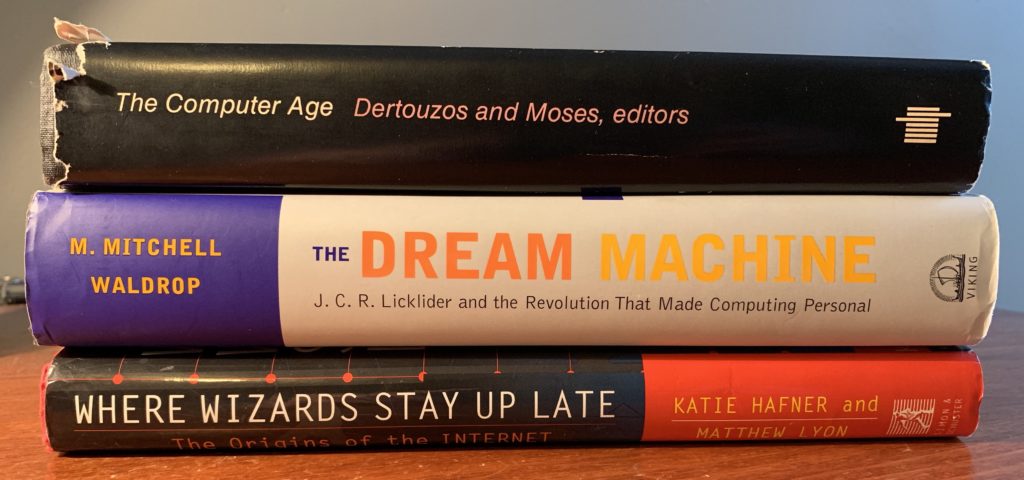

Sometime around 1998, I read a wonderful history of the Internet by Katie Hafner and Matthew Lyon called Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet. And through that history, I was introduced to the work and writings of the other bookend of my thinking about technology and politics: J.C.R. Licklider.

In 1962, Licklider was the Director of the Information Processing Techniques Office at the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPANET was the predecessor of the Internet) and is considered among computer science’s most important figures. His prescient writings about computers, networks and their impacts, well, sort of blew my mind. The below excerpt from Where Wizards Stay Up Late captures the key Licklider (Just ‘Lick’ to many) prediction that I’ve never forgotten:

“The idea on which Lick’s worldview pivoted was that technological progress would save humanity. The political process was a favorite example of his. In a McLuhanesque view of the power of electronic media, Lick saw a future in which, thanks in large part to the reach of computers, most citizens would be “informed about, and interested in, and involved in, the process of government.” He imagined what he called “home computer consoles” and television sets linked together in a massive network. “The political process,” he wrote, “would essentially be a giant teleconference, and a campaign would be a months-long series of communications among candidates, propagandists, commentators, political action groups, and voters. The key is the self-motivating exhilaration that accompanies truly effective interaction with information through a good console and a good network to a good computer.””

The book didn’t directly cite where this passage from Licklider came from, but the very next paragraph described his “seminal paper”, Man-Computer Symbiosis. Written in 1960, Man-Computer Symbiosis describes Lick’s imagined future where “the main intellectual advances will be made by men and computers working together in intimate association.” The paper is considered a key text in the field of computer science. (For a recent look back, check out this article, Another Look at Man-Computer Symbiosis by David Scott Brown, 1/3/18).

Given the placement of this mention of Man-Computer Symbiosis, immediately following the passage about “the political process”, I naturally imagined it as the source of the passage. Alas, it is not. And so for years I have shared this excerpt of Licklider’s predictions on the impact of computer networks on our political process as I originally found it in Where Wizards Stay Up Late, still uncertain of its origin.

In 2001 a biography of J.C.R. Licklider titled The Dream Machine: J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution That Made Computing Personal by M. Mitchell Waldrop was published. I have a copy signed by the author at a bookstore event. And for years, my copy sat on a bookshelf, always hovering near the top of my ‘to-read’ pile, but never quite making it to the top spot until I finally finished it last year. And it led to a major breakthrough in my hunt for the source of Licklider’s ‘political process’ writing, and in doing so, to the reason that I owe J.C.R. Licklider an apology.

In The Dream Machine, Waldrop also singled out the same bit of writing that had captured my imagination for years since first reading it in Where Wizards Stay Up Late.

“The key is the self-motivating exhilaration that accompanies truly effective interaction with information and knowledge through a good console connected through a good network to a good computer.”

In my blog post, I wrote;

Information itself can be good or bad, and technology cares little about which sort it disseminates and propagates. Avoiding ignorance, as Jefferson’s hopes for civilization require, presume an ability to recognize and reject bad information to avoid being ill-informed. Licklider describes a ‘good console’ and a ‘good network’ as needed for facilitating an ‘effective interaction with information,’ but not specifically ‘good information.’ An effective interaction with bad information is equally likely. Ignorance born of bad, but effectively delivered information can and does do damage to our political process.

Waldrop foretold my connection between Thomas Jefferson and Licklider, and also my notion that Licklider had innocently overlooked the possibility of ‘bad information’ in his formulation. Waldrop wrote of Licklider’s vision, “It was a vision that was downright Jeffersonian in its idealism, and perhaps in its naïveté as well.”

More importantly, Waldrop did me the favor of citing the source of this passage. It came from a chapter titled Computers and Government that Licklider contributed to an anthology published by MIT Press in 1979 titled The Computer Age: A Twenty-Year View. (In their defense, the authors of Where Wizards Stay Up Late included this volume in their bibliography, they just hadn’t directly connected it to the ‘political process’ passage.)

So to the Internet I turned, where I located and purchased a copy of The Computer Age: A Twenty-Year View, so I could at last drink of Licklider’s predictions for ‘Computers and Government’ direct from the source.

And guess what?! When I found my treasured passage in Licklider’s 40-page chapter in its original content, I found that in the very next paragraph he addressed exactly the sort of potential bad actors and bad information that I had previously accused him of naively overlooking.

And THAT, is why I owe J.C.R. Licklider an apology. Licklider was fully aware of the potential pitfalls and dirty tricks that the network he was still helping to build, and he described several of those potential problems with the same level of prognosticative detail that characterized so much of his writing. I’m sorry I suggested that this was a blind spot in his thinking.

And to correct this mis-characterization which I have perpetuated, below is a fuller excerpt from two out of forty pages that contained my oft-repeated political process passage, and Lick’s dose of reality that followed it. I have bolded the original passage, and added a few bracketed notes throughout.

From Computers and Government, a chapter contributed by J.C.R. Licklider to The Computer Age: A Twenty-Year View (1979, The MIT Press).

Computers and politics

It is technically possible to bring into being, during the remainder of this century, and information environment that would give politics greater depth and dimension than it now has [Remember, the NOW he’s writing about is 1979]. That environment would be a network environment, with home information centers (which would of course include consoles as well as television sets) as widespread as television sets are now. The political process would essentially be a giant teleconference, and a campaign would be a months-long series of communications among candidates, propagandists, commentators, political action groups, and voters. Many of the communications would be television programs or “spots,” but most would involve sending message via the network or reading, appending to, or setting pointers in information bases. Some of the communications would be real-time, concurrently interactive. The voting records of candidates would be available on-line [Generally speaking, they are], and there would be programs to compare the favorable information about themselves and critical assertions about their opponents. Charges would be documented by pointed to supporting records. Under the watchful control of monitoring protocols, every insertion would be “signed,” dated, and recorded in a publicly accessible audit trail [But who makes and monitors the monitoring protocols?]. Because millions of people would be active participants in this process, almost every element of the accumulating information base would be examined and researched by several proponents, several opponents, and perhaps even a few independent defenders of honesty and truth. Nothing would be beyond question [The opposite has become the norm, EVERYTHING IS QUESTIONED], and the question would go, along with whatever answers were forthcoming, into the accessible record. Interactive politics would function well only to the extent that the citizens were informed, but it would inform them as the had never been informed before.

Such an environment and such a process would undoubtedly open up new vistas for dirty tricks. However, by bringing millions of citizens into active participation through millions of channels, it would make it more difficult for anyone to control and subvert any large fraction of the total information flow. It would give the law of large numbers a chance to operate, and within its domain tricks would be more like vigorous expressions of the feelings of individual citizens – unless, of course, a government [Russia, China] or a syndicate [Facebook] controlled and subverted the whole network. The clandestine artificial-intelligence programs, searching through the data bases, altering files, fabricating records, and erasing their own audit trails, would bring a new meaning to “machine politics.”

It is not likely that any agency of the U.S. government will deliberately develop anything approaching computer-based politics, because congressman have such a reactionary attitude toward meddling with their traditional political process [Not so in today’s hyper partisan atmosphere in Congress]. However, the development of networking for other purposes may create the facilities required for highly participatory political interaction. This is yet another reason for emphasizing the importance of computer system and network security, since it would be absolutely essential to orderly an effective interactive politics; one might even say that the security would have to be Watertight [A Watergate related pun?

Other issues and problems

The theme of government use of computers to control or repress the people deserves much more extensive examination, but the following notions will suggest some of the topics it might pursue:

- Programmed instruction subverted to brainwashing in favor of a regime in power [Russian trolls and bots]

- Programmed monitoring and censorship, achieved with the aid of natural language understanding programs

- An automatic system that appends the government’s refutation to every article or program that is judged by the monitoring program to be critical of the government

- Automated checking of adherence to government-prescribed schedules of activity and avoidance of government-proscribed activities

- Automated compilation of sociometric association nets, showing who communicates with whom, who participates in what activities, who views which programs, and so on [Facebook]

[then, after much more good and insightful stuff, too much for me to re-type, Licklider concluded his chapter thusly]

Finally, the renewed hope I referred to is more than a feeling in the air. As a few thousand people now know – the people who have been so fortunate as to have had the first reich experience in interactive computing and networking – it is a feeling one experiences at the console. The information revolution is bringing with it a key that may open the door to a new era of involvement and participation. The key is the self-motivating exhilaration that accompanies truly effective interaction with information and knowledge through a good console connected through a good network to a good computer.